An ELI5 summary of how and why SVB failed, and whether there were any red flags that retail investors could have used to foresee this. What can we, as investors, learn from this incident?

Spoiler alert: it would have been incredibly difficult. This article examines how, in an alternate reality, SVB may not have collapsed after all.

Last week, we watched as the 16th largest bank in the US collapsed. Up until last Friday, it was the preferred bank for startups and tech firms, worth over $200 billion and was a stock market darling (having been recommended by various “gurus” and investment subscription services) that benefited from the pandemic.

Until it all came down to zero.

SVB looked to be a darling stock for most

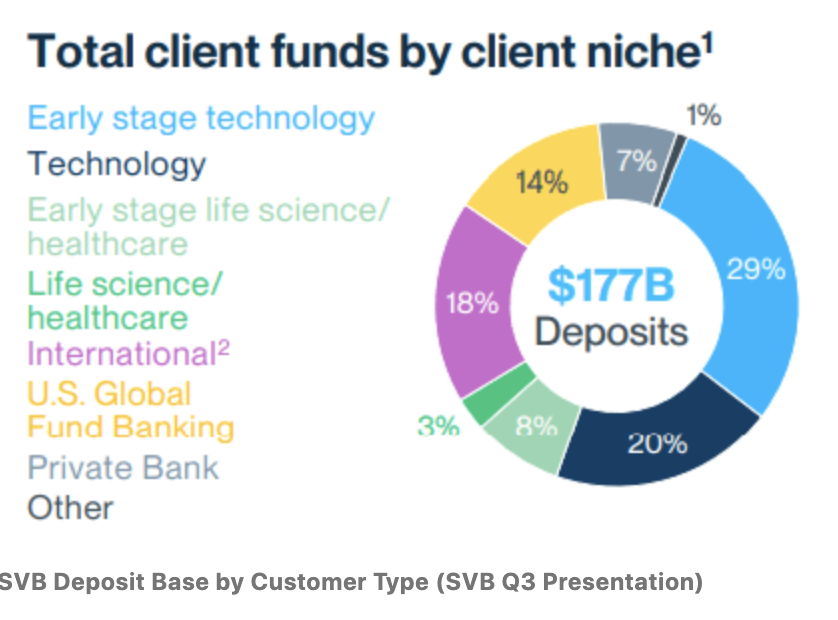

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) Financial provided banking services to start-ups, who put their funds raised from private equity or venture capital firms into the bank and use it for operating expenses, payroll, etc.

From a business standpoint, SVB delivered tremendous growth – from $6 billion in interest-earning assets in 2007 to $210 billion in 2022 – an approximate 27% annual growth rate.

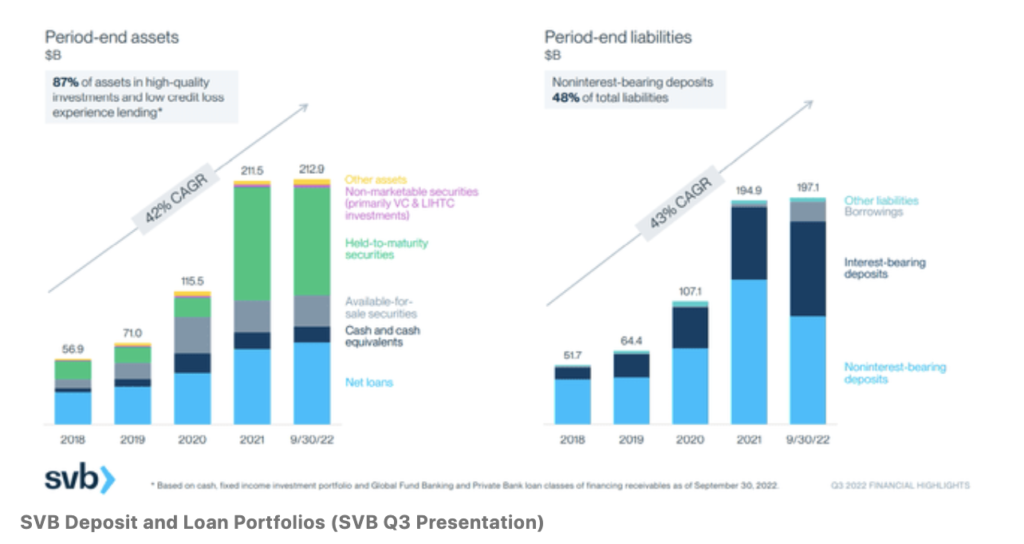

SVB’s growth in deposits and loans held steady at 10% – 20% in the years after the Global Financial Crisis. And then from 2018 onwards, the growth rates accelerated to around 40% CAGR levels.

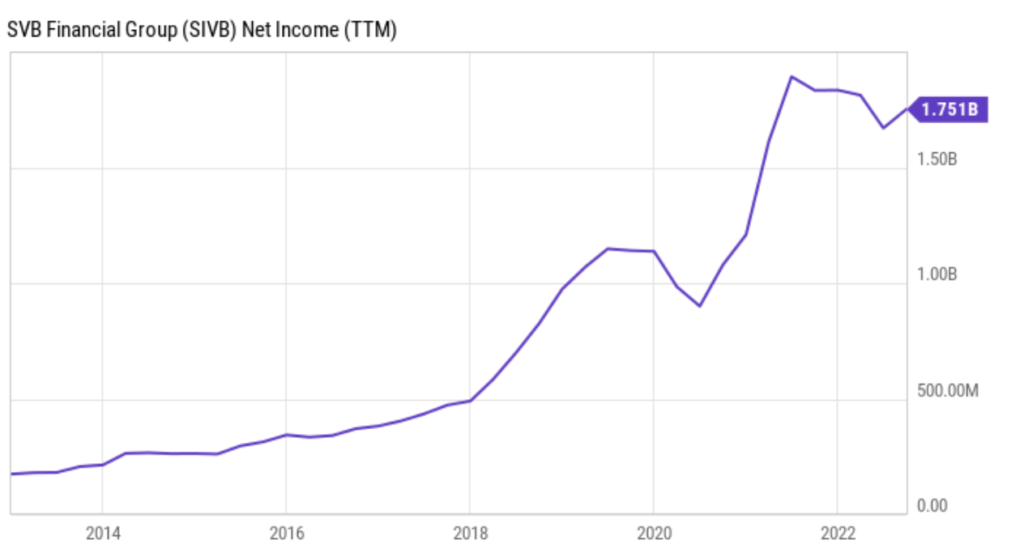

This also translated into solid net income growth for the bank:

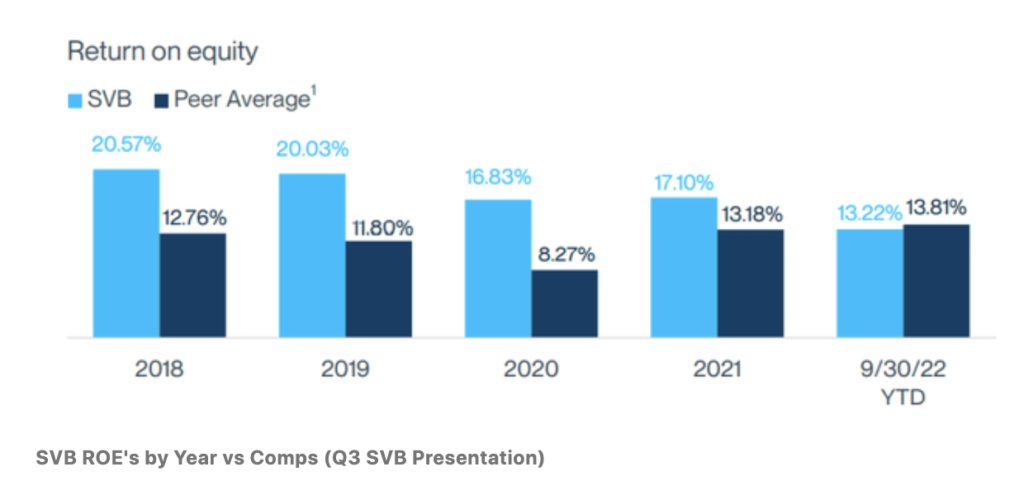

As a result, SVB’s stock typically traded at a premium to other banks because of its higher growth rates and outstanding returns. In the last decade, its return on equity (ROE) outpaced even banking peers like JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America.

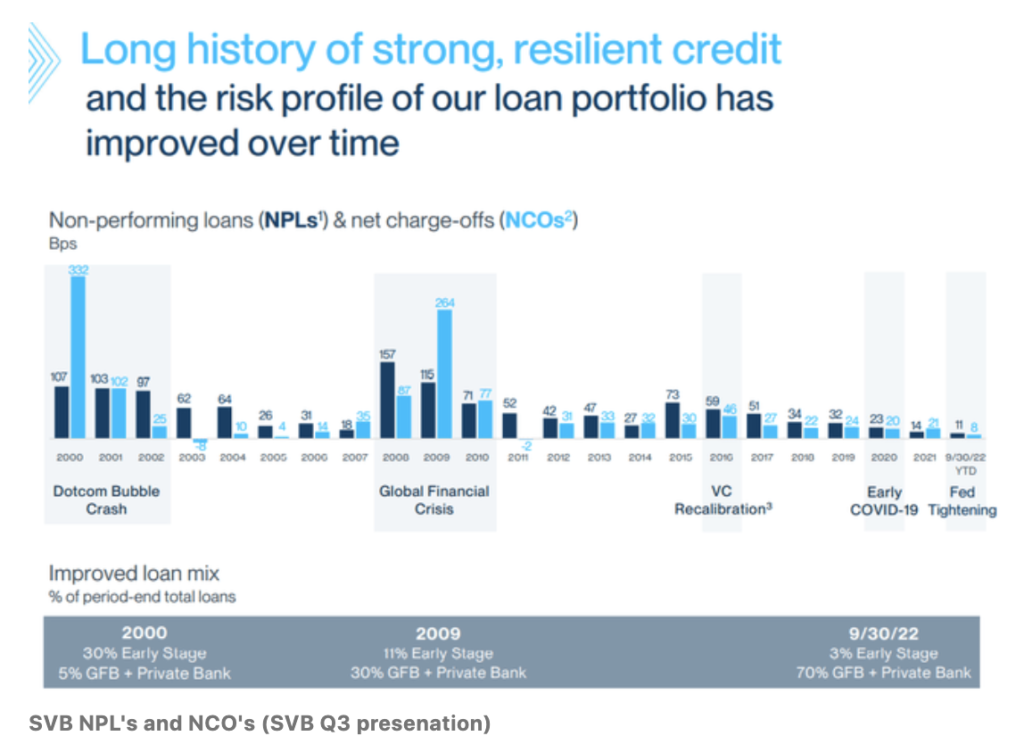

After the subprime mortgage crisis that caused the collapse of Lehman Brothers, investors have been paying closer attention to the loans portfolio of banks. In SVB’s case, management reassured investors that their loans were of low risk (although some had their doubts about whether a recession would eventually lead to the start-ups who loaned from SVB to default on their payments).

From a credit perspective, SVB’s loans and bonds were of a good credit quality; their data showed a low probability of default. But the red flags were starting to show.

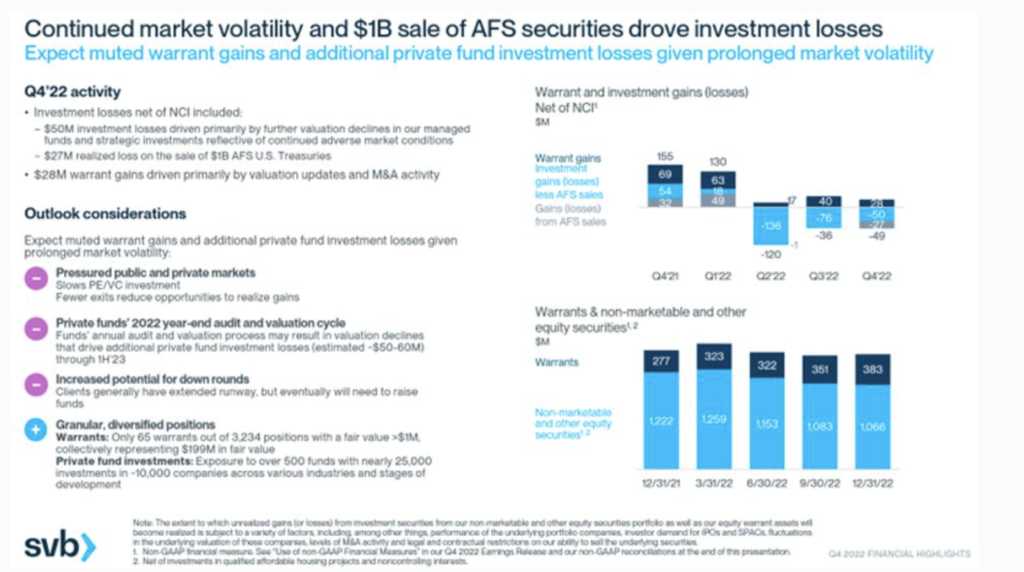

In Q4 2022, SVB disclosed significant investment losses, which included a hit of $27 million on the sale of $1 billion of US treasury bonds.

And then in March, the darling stock crashed within 24 hours.

How did Silicon Valley Bank collapse so quickly?

How it was possible for such a large bank to collapse in just 48 hours, in less time than what it took for crypto Terra Luna / USDT to go to zero last year?

The primary reason for SVB’s rapid collapse (in no less than 48 hours) was due to a bank run.

The secondary reason was due to management’s missteps (I counted at least 3).

In ELI5 (explain like I’m 5) speak, a bank run occurs when clients want to withdraw more money from a bank than it has available.

Bank run = when customers withdrawing money > money available in the bank.

How did the bank run out of money?

Well, when you and I (depositors) put money in a bank, the bank generally pays us (a low) interest on it while taking our funds to reinvest in financial products with a higher rate of return – such as through loans, equities, fixed income products, etc.

The difference between what the bank pays us vs. what they earn = their profits. And as of December 2022, SVB’s net profit margin was still juicy at 22.05%.

But underneath the hood, the reality was that SVB had received so much deposits during the last few years (thanks to the run-up in VC funding through the pandemic) that it wasn’t able to loan them out fast enough.

So, instead of making risky loans (such as to borrowers with poor credit but with high urgency needs), SVB decided to invest in fixed-income investments – including long-dated US government bonds – which were much safer.

This was a management misstep, although not yet painfully obvious at that time (given the choices).

Now, if interest rates had remained low, this wouldn’t have been a problem. But then the Federal Reserve decided to raise interest rates, and they raised it fast.

Interest rates went from effectively zero to almost 5% in less than a year.

This caused 2 problems for SVB:

- The higher interest rates also caused SVB’s fixed income investments to drop rapidly in value.

The second management misstep here was that SVB failed to execute interest rate swaps.

Bonds have an inverse relationship with interest rates: when rates rise, bond prices fall. Hence, SVB started seeing huge losses on its bond portfolio. One strategy to deal with that would be to hedge via interest rate swaps, but in its FY2022 financial report, SVB reported virtually no interest rate hedges on its massive bond portfolio.

While risky, this still wouldn’t have been a problem if they were able to simply hold until the bonds mature, as it would get back its capital then. However, with cheap funding drying up, SVB’s customers were also starting to run into problems themselves, and needed to withdraw its deposits to keep their business alive. As a result, SVB’s deposit base started shrinking significantly, with non-interest-bearing deposits falling by 25% from December 2021 to September 2022.

In the last quarter, SVB’s non-interest-bearing deposits declined by 36%.

As SVB started running out of liquid funds to meet these withdrawal requests, the bank had no choice but to start selling its bond investments. But who on earth would want to buy bonds with a low 1+% coupon rate when they can get a higher rate T-bill today? And hence, SVB had to sell the bonds at a steep discount in order to liquidate its locked-up funds.

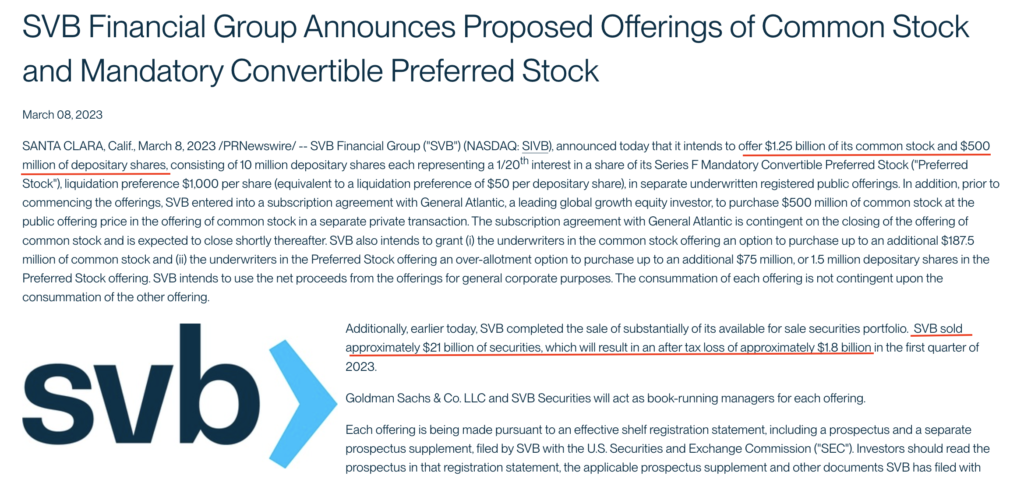

Then, on 8th March, SVB announced that it had sold a total of $21 billion of its investments at a loss in order to meet withdrawal demand, and that it was going to issue equity to raise additional capital.

This was the third management misstep: its communication failure.

In an alternate reality where the bank had managed its communications better (and not in such a factual, straightforward manner that clearly caused depositors to panic), we can only imagine one where the bank run may not have happened.

But SVB’s announcement spooked depositors, who started withdrawing their capital due to worries over the bank’s illiquidity. A big part of the panic was also because many depositors had more than $250,000 in SVB accounts, which are not insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Within 24 hours, nearly 25% of all of SVB’s deposits had been withdrawn (9th March).

On 10th March, the bank was seized by U.S. regulators and the FDIC ordered its immediate closure.

The whole collapse unravelled in just under 48 hours, making it the biggest bank failure in the US since the global financial crisis.

Did the US government bail out SVB? No.

It was a painful weekend of waiting with bated breath, but on 13th March, regulators stepped up to guarantee all the remaining deposits at SVB (including uninsured funds) and unveiled a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

The BTFP is designed for banks to be able to borrow funds backed by government securities to meet withdrawal demands from deposit customers. This prevents banks (in the aftermath of SVB) from being forced to sell government bonds or other assets that have been losing value due to rising interest rates.

With this move, it is clear that the regulators know that the public is spooked and are trying to prevent similar bank runs at other institutions.

But only the depositors are protected; shareholders of SVB and unsecured creditors aren’t.

This was not a bailout. The government is not saving SVB – it will stay collapsed and wound up with its remaining assets dispersed to customers and creditors.

Now that we all understand the backstory of SVB and how it was possible for such a large bank to collapse so quickly, what’s more important is what we can possbily learn from this. Hence, the bigger question here is:

Could retail investors have spotted the red flags?

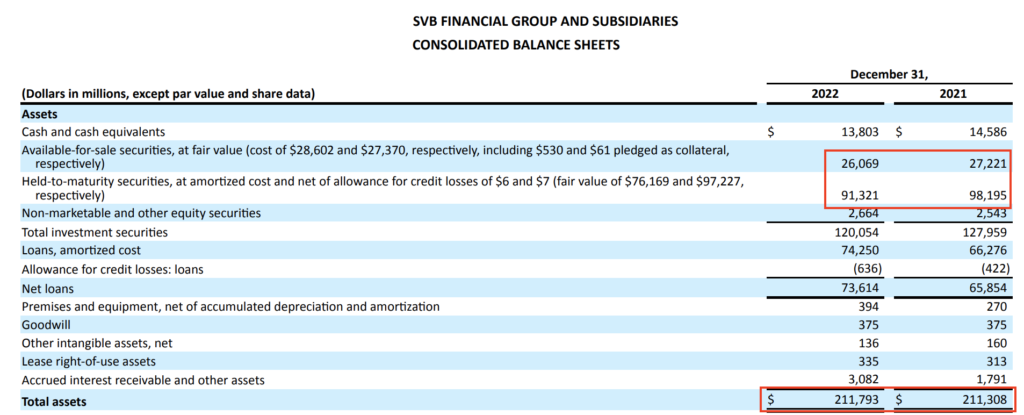

Firstly, let’s be frank and acknowledge that not everyone is capable of understanding the (often convoluted) banks’ financial statements and notes. If you had looked at its balance sheet, there didn’t seem to be too much to be concerned about.

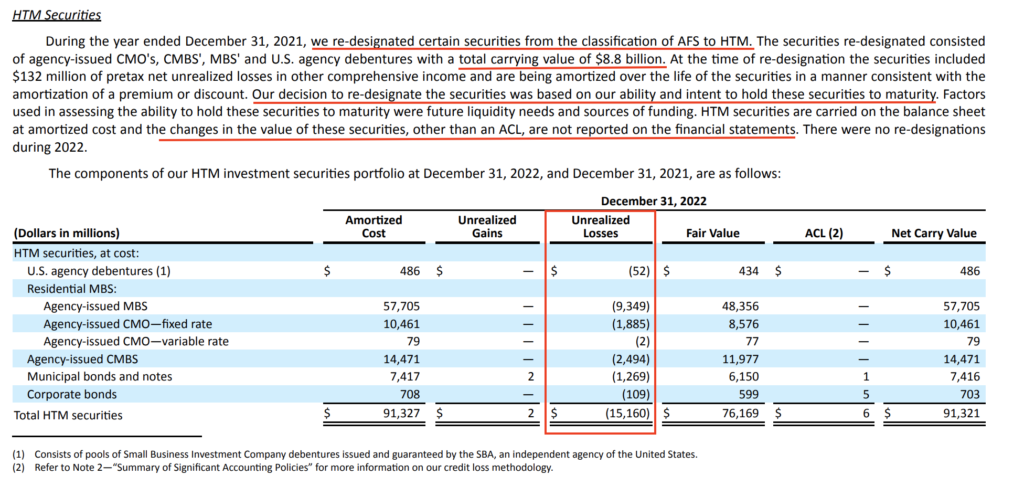

SVB was also not required to reprice their Held-To-Maturity (HTM) assets based on current market prices unless they sold them, so the impact of its declining bond portfolio value was not entirely clear. One could only guess, but remember, this wouldn’t have been a problem IF the bank hadn’t needed to sell bonds off to meet withdrawal demands.

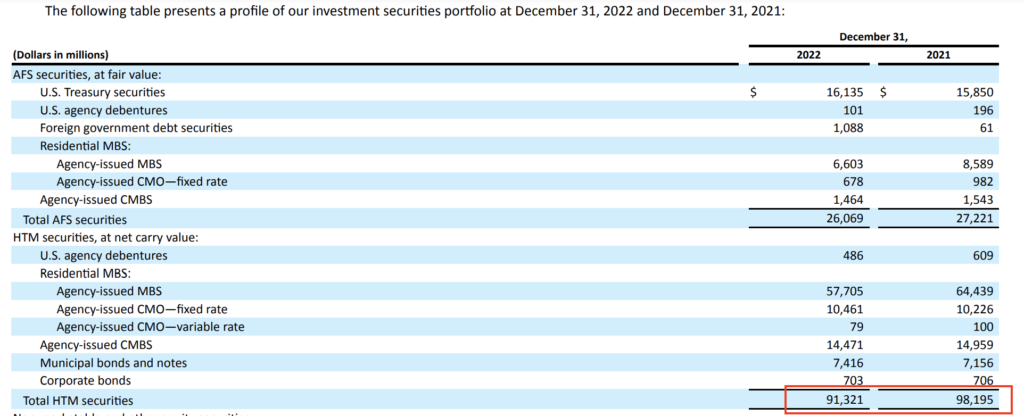

Only for the sharp-eyed investors who bothered to look deeper into the notes to the financial statements, page 125 revealed a US$15.1 billion drawdown. If you had then deducted that from the reported value of US$91.3 billion on the balance sheet , you could have then realized that the marked-to-market value of the entire HTM securities portfolio should have been US$76.2 billion instead.

Even with this, you still wouldn’t have been able to tell if the US$15.1 billion drawdown was due to the HTM assets maturing, or for some other undisclosed reason. And if you looked deeper, page 64 shows you what the HTM assets consisted of – not exactly enough to set off red-hot warning signs.

Some people blame this on the relaxed risk management requirements for banks under $250 billion in assets, which was signed into law in 2018 by President Trump (which eased the requirements put in place in the aftermath of the GFC under the Dodd-Frank and the Consumer Protection Act).

As a result, SVB was not required to disclose how much it had in high-quality liquid assets to help it cover net cash outflows (if depositors started withdrawing en masse), so it wasn’t something that retail investors could pick up on.

Crucially, this means there was no way to know whether SVB had enough to prevent a bank run, even if investors were concerned that the start-ups SVB served might start withdrawing their funds. Dilution of existing investors was a more probable scenario (due to SVB raising new capital to fund liquidity needs).

What’s more, 2 weeks before SVB’s collapse, its CEO Greg Becker sold ~12,500 of his company’s shares.

I suppose if an investor who had been vested and had been monitoring the company closely, then spotting the combination of red flags may have helped you to sell off before its collapse:

- SVB started reporting a narrowing deposit base since Dec 2021

- SVB’s customers are mainly tech firms and start-ups, who have been laying off workers and started defaulting over the past year.

- 16.5% of its (HTM) bond portfolio seemed to have declined in a single financial year. (A sign that only eagle-eyed investors with knowledge of how HTM asset values work and are reported would be able to pick up on.)

- The Form 4 filing showing SVB’s CEO selling his shares to net $2.2 million

But even with that, it wasn’t so easy. After all, the stock was being touted as “cheap” by many subscription services, and until Wednesday, Moody’s and S&P Global had Silicon Valley Bank as an investment grade issuer – meaning SVB had a low probability of default and loss severity.

Only Thursday (after the announcement) did Moody’s and S&P Global changed their outlook on the bank from stable to negative.

TLDR (Hindsight Review):

1. Investors had no way to know whether SVB had enough liquid assets to prevent a bank run, due to prevailing regulatory reporting standards.

2. SVB’s declining bond portfolio losses were also unclear, since the bank wasn’t required to report it until sold.

3. There were hardly any glaring red flags in SVB’s loans portfolio, given the low ratio of non-performing loans.

4. The $2.2 million stock sale by SVB’s CEO 2 weeks before its collapse could have been a warning sign, but not a conclusive signal.

5. You would have to go against the prevailing sentiment that SVB was an undervalued, high-quality financial institution whose share price got battered only because of the unfortunate macro-economic climate for tech firms.

6. Even Moody’s and S&P Global rated SVB as investment grade i.e. one with a low probability of default and loss severity.

So could this have been foreseen? Not exactly.

The way I see it, SVB’s collapse ultimately comes down to a combination of 2 crucial management mistakes:

- Investing in the wrong assets, and then failing to hedge that as interest rates rose

- Poor handling of SVB’s communications (on 8th March), which spooked its depositors and triggered a bank run

Even if you were a savvy investor who could spot #1, no one could have predicted #2 with accuracy. In fact, no one did.

It is always easy to say (with hindsight accuracy) that there were glaring red flags that investors missed. But after reviewing all the data and analysis, I find that this wasn’t necessarily the case with SVB.

As you can see, it would have been difficult to predict SVB’s collapse with certainty. Because if #2 had been handled better (and you guys can debate over what that entails, such as raising funds from other banks or institutions instead of selling their bonds, or even tweaking the way they made their announcement to make the illiquid situation less painfully obvious), a bank run may or may not have happened.

And in that alternate reality, who knows? SVB might have risen from the flames to reclaim its status as a darling stock after all.

Author’s Note: I do not own shares in SVB and was never invested. However, this incident definitely raises new learning points for us investors to take note of. While watching the crisis unfold, the biggest question at the back of my mind was whether retail investors could have foreseen this, and thus prevented their losses.